Welcome to Sapienta Cyprus Reflections. It is free for now. More about this subcategory of Sapienta Cyprus Snippets here.

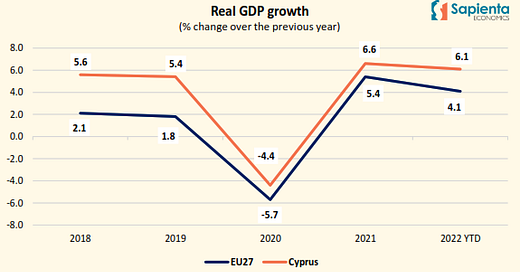

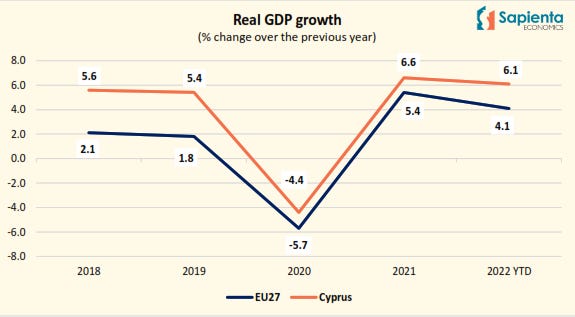

For most of this year I have been telling subscribers to my flagship Sapienta Country Analysis Cyprus that the widely cited real GDP forecasts put out by the IMF and European Commission earlier this year were out of date. By September I was telling them that I would probably need to revisit my own forecast once the third-quarter figures came out in November. Sure enough, this week, the “flash estimate” from the statistical service, Cystat, reported that real GDP in the third quarter had expanded by a seasonally adjusted 5.4% compared with the same period of the previous year. This brought the average growth rate for the first three quarters of 2022 to 6.1%.

The latest statistics underline something quite extraordinary about the Republic of Cyprus economy, namely its capacity for bouncing back after adversity. This year, after Russia invaded Ukraine and as sanctions tightened, Cyprus lost its second largest tourism market, probably its largest market for business services and, like elsewhere, saw inflation rates not seen for decades. In March, my worst-case scenario had the economy shrinking by 0.4% this year, while my baseline scenario at that time was for real GDP growth of 3.6%. But thanks in part to a post-lockdown tourism bounce, the latest figures suggest that growth in 2022 is more likely to be close to 6%.

This is not the first time that the Cyprus economy has shown such resilience. The economy took just one year to regain its size after the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, two years to regain it after the severe financial crisis in 2013 (although it did take longer to regain its level before the 2008 global financial crisis) and just two years to regain its size after the massive shock of the 1974 invasion.

So what is the secret to the resilience of the Cyprus economy?

Secret sauce 1: resilience to marauding armies

My usual reply to diplomats or international journalists is that thousands of years of marauding armies have made Cypriots rather resilient to external shocks: another foreign army comes and knocks over your house; you pick yourself up the next day and start again.

Part of this resilience is that, even if your own generation might not know how to grow food, you know someone who does. You hoard food and supplies (just in case), you keep cash in unexpected places (just in case) and you memorize back-routes to the village house (just in case). I saw this with my own eyes watching Cypriots respond to the 12-day bank “holiday” in March 2013.

(This instinct also means the primary focus tends to be on short-term survival rather than long-term strategy. But that is an article for another day.)

Secret sauce 2: property ownership

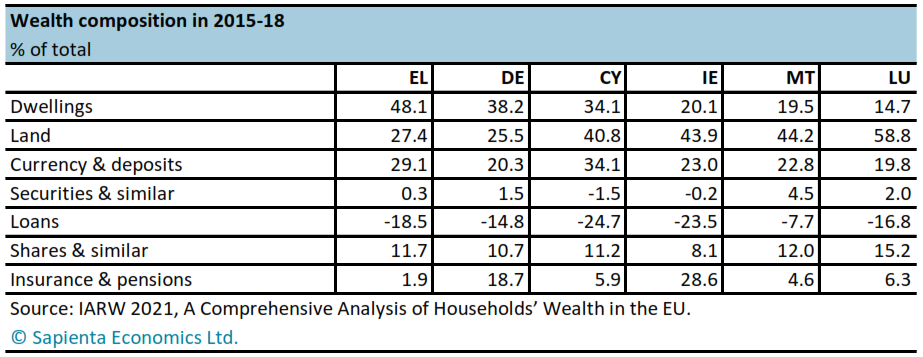

The second ingredient of the secret sauce is, I believe, widespread land property ownership. According to a 2021 study by Eurostat and Istat officials, while households in Ireland, Malta and Luxembourg have on average more land than those in Cyprus, residents of Cyprus have more homes (dwellings), as well as more money in the bank (see table). Add to that how difficult it is for banks in Cyprus to come and take your house if you decide to spend the mortgage money on your daughter’s university fees, and you can see why external shocks don’t tend to end up with people on the street.

(This probably also means that banks will inevitably end up owned by hedge funds. But that, too, is an article for another day.)

Secret sauce 3: publicly funded salaries?

I have a third, more speculative reason, and that is the proportion of the workforce that is essentially earning decent money from publicly funded salaries. By publicly funded salaries I mean all of the public sector as well as most of higher education and healthcare. The public, education and health sectors together accounted for 19.5% of employment in mid-2022. Yet extrapolating from their earnings in 2020 (latest available data), you can see that the publicly funded sector accounted for 25.1% of earnings. If you add bankers, that rises to 33.4%, or an even higher 43% if you add professional services (lawyers and accountants). This is what one might term the “comfortable sector”. Most of them have automatic and/or partly inflation-linked pay rises, and they are the ones who keep on spending in shops, restaurants and on takeaway coffees regardless of what happens to the wider economy.

I call this reason speculative because it would require digging into the employment and pay statistics of other countries to see whether the phenomenon is different elsewhere. For the moment, my hunch is that, relative to the average salary, workers in the public sector, education and health sectors in Cyprus earn more than their European counterparts, while those in the financial and professional services sectors probably earn less than in financial capitals (meaning: a lower multiple of the average salary) but their jobs are more secure.

Secret sauce 4: hidden wealth?

Another potential reason is hidden wealth or untaxed income. My suspicion is that this proportion has probably shrunk since 2020 for two reasons. First, most medical specialists, who took cash payments and rarely gave receipts, have shifted to the national health system (GESY) and are now declaring incomes closer to their actual earnings. Second, retail outlets have been forced since 2020 to introduce point of sale (POS) machines. In addition, the mass closure of bank branches along with the disappearance of their cash-withdrawal machines means that all of us are using cards more often to pay for things that used to be paid for in cash, even if it is clear that most “odd job” work is still done for cash. A third reason to assume less hidden wealth than in the past is that banks have become much stricter about accepting cash deposits or even cash withdrawals. I hope I am not being naïve, but my view is that, while some of those at the top of the food chain still seem to find endless ways to engage in shady practices, it is much harder these days for those lower down the food chain to hide money from the tax authorities.

Actual sauce: small size

Last but not least, a clear and non-speculative reason for fast rebounding growth is economic size. The Cyprus economy is just €24bn, making it the second smallest economy in the EU after Malta. If your starting size is €24bn and you expand an additional €2bn, you have grown by 8.3%. If your starting size is €240bn (something closer to Finland) and you expand an additional €2bn, you have grown by only 0.8%.

As the saying goes, small is beautiful.

Secret sauce! Love it! Brilliant read!

Great read Fiona! Very interesting thoughts and insights.

> This instinct also means the primary focus tends to be on short-term survival rather than long-term strategy. But that is an article for another day.

I'd be very interested to see your thoughts on the above.