This is my latest video. You can find all of the reports and infographics and videos I refer to at the About us section of the Sapienta Eonomics website if you scroll down to publications.

The full transcript is below.

If you want my premium monthly in-depth product, check out Sapienta Country Analysis Cyprus and other deep-dive reports here or single copies here. And if you can’t afford those but want the executive summary only for just €100/year*, you can find that here on Substack, at Cyprus Pocket Brief.

Or support this publication, Sapienta Cyprus Snippets, for just €49 per year.*

*Monthly payments are a massive administrative headache, so since I can’t switch them off I have effectively banned them by setting the monthly price the same as the annual.

TRANSCRIPT

How have Cypriots on both sides of the island paid for the Cyprus problem? Let’s take a look.

Many years ago, maybe in 2006, I approached the UN with an idea to try and calculate the cost to the economy of a divided Cyprus.

The boss at the time, Michael Moeller, encouraged me to think instead about making it more positive: to make it about the benefits, not the costs.

To cut a long story short, in 2008 that culminated in the publication of the first of the Day After reports with Praxoula Antoniadou Kyriacou and Ӧzlem Oğuz.

I think this broke a taboo because it was the first time that Greek Cypriots had heard that a solution of the Cyprus problem might actually be good for the economy. It was published just days after Demetris Christofias got elected. And because there was a pro-solution leader on the other side, Mehmet Ali Talat, there was a lot of hope about putting the country back together again.

In 2009 we looked at how you could fund a solution of a Cyprus settlement.

And in 2010 we looked at the peace dividend for Turkey and Greece.

Then in 2014 I got two academics on board to take a different approach, where we produced what we called Revisiting the Cyprus Peace Dividend.

And then the final one, published in February 2020, right before the Covid-19 lockdown, was called Delivering the Cyprus Peace Dividend. This included low, medium and high forecasts, Monte Carlo simulations to test how robust the forecast was, a focus on gender and lots of other recommendations of things to put in place to ensure that you could make the peace dividend as big as possible and address any potential losers.

We also had 4 pretty infographics in three languages.

And 3 videos in three languages.

You can download them all here on the “About us” section of the Sapienta Economics website.

It was a massive undertaking. And to be honest that is why I haven’t approached it since.

BUT it does give us something of an answer to what is the cost of division. Because in many ways the amount you can make WITH a solution is also the same as the amount you are losing WITHOUT a solution. I’ll get back to that in a moment.

But first let me look at some other clear costs of division. And let me start with the Turkish Cypriots.

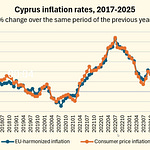

One clear loss is inflation. In 2002 we had what we thought was pretty painful inflation rate in the southern part of the island of 8.1%. But in the North inflation rate hit 99.7%.

Incidentally this is why we now see an increase in the number of Turkish Cypriots crossing to the south and a decrease in a number of Greek Cypriots crossing north because prices of basically everything except fuel is cheaper on this side of the island, in the south.

Just to emphasise, the difference in inflation isn’t just one year. It’s on average a massive difference in inflation rates. This is because northern Cyprus uses the Turkish lira, which weakens all the time, and that puts up your input prices. So while the average 10-year inflation rate in the south was just 1.4% from 2015 to 2024, it was 16.3% in the northern part of the island.

So, Turkish Cypriots pay through inflation. And high inflation holds back your economic growth rates. The average real GDP growth rate in the south in 2015-2024, despite Covid-19, despite 2015 being the tail end of the financial crisis, was 4.9%.

In the north, despite very strong population growth, which normally boosts your economic growth, the average was only 3.1%.

What this translates into is lower GDP per person—essentially lower incomes. Now, you might say, “Oh I heard that the minimum wage in northern Cyprus is now higher than it is in the south.” That’s true. But a far far larger proportion of the workforce gets only the minimum wage in northern Cyprus, whereas in the south it is a lot smaller proportion.

So on average people in northern Cyprus are not as well off as they are in the south.

On top of that, you can see that Turkish Cypriot independence, or Turkish Cypriot economic agency if you like, is weakening over time. Why? Because Turkey is an ever larger share of trade. It is 80% of tourists and about half of all foreign students. This is all a by-product of a court case in 1994, which in turn is a by-product of the Cyprus problem.

There are also other issues. The average length of stay of tourists on northern Cyprus is only about 3 days, compared with almost 9 days in the south. What does this mean? Casino tourism. People staying in hotels and gambling all weekend and not going out and spending money in restaurants outside.

Now let’s have a look at the cost for Greek Cypriots.

This is more subtle and not so easy to quantify. But I think the really obvious one is the impact on electricity prices. Let me explain.

So let’s start with the fact that natural gas is much cheaper than diesel or mazut. At the moment about 75% of electricity consumption in Cyprus diesel and mazut—heavy fuel oil. Forget how much solar energy is being produced. It is how much is actually used that matters.

And as we can see from Charles Ellinas, who writes frequently in lots of different newspapers about the energy issue, natural gas is cheaper because we pay less for emissions. Gas is less dirty than diesel and mazut and also is just generally cheaper, okay?

Now, Cyprus has discovered some natural gas. But somehow it has never been produced. Everybody else discovers gas and goes on to produce it. But not in Cyprus. Every year we find out that all those promises of producing natural gas have not come to pass.

So Aphrodite was discovered in 2011. 14 years later it still on the ground. Yes, Chevron is undertaking studies at the moment but we still don’t know if it’s going to put money into actually getting it out of the ground.

As I mentioned in an earlier video, ENI was supposed to submit its development plan for Cronos earlier this year and it looks like that hasn’t happened either.

So my conclusion of all this is that the Cyprus problem gets in the way of getting gas out of the ground and onto market quickly.

The Cyprus problem is also very clearly stalling the Great Sea Interconnector, as you will know if you’ve looked at all of the rows going on between Greece and Cyprus about it. And this means that we can’t draw on cheaper energy sources. We are in energy island stuck with our expensive diesel under expensive mazut.

And the reason why I think gas is also being affected by the Cyprus problem is what Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said the other week at the UN General Assembly. He said basically anything that you do in Eastern Mediterranean, if you try to leave out Turkey, Turkey will stop it. And I’m not defending what he is saying but this is the Realpolitik of today’s geopolitics, where, more than ever before, “might is right”.

So without a Cyprus solution you may not going to get gas out of the ground, you are not going to have an interconnector, so you will stay with the highest electricity prices in the EU, at least for medium-sized businesses.

There is also a case to be made that the Cyprus problem also decreases the independence, or sovereignty if you like, of Greek Cypriots because of increasing dependence on Greece. Greece is increasingly visible in retail, in the banking sector, in the coffee chains etc. Why is that? It’s because it basically has no competitor because there is no trade with the nearest trading partner, namely Turkey. Lack of competition tends to put upward pressure on prices.

A final also somewhat intangible cost of the Cyprus problem is a by-product of the fact that the position of vice-president is vacant. It means—and academics of written papers on this—it means that the president of the Republic of Cyprus is extremely powerful relative to other leaders in Europe and even the United States, okay? It means there are fewer checks and balances.

And I think we’ve all seen what has turned into the project for importing liquefied natural gas (LNG), which would also have cut our electricity prices, is under criminal investigation by the EU. The Great Sea Interconnector is also under criminal investigation by the EU.

So I’m not saying that corruption would disappear if you unite the island. But certainly there is a structural element in a divided Cyprus that makes corruption far more likely, OK?

Now back to our Peace Dividend. What did we find back in 2020? We found that, GDP could be up to 1.4 times higher with a solution than without one. It would be about €17bn higher, which at today’s prices is about €20bn higher.

Growth would be about 1.8 percentage points higher, which is a lot when it accumulates over a number of years.

And importantly for Turkish Cypriots, their incomes would shift far closer to Greek Cypriot ones.

In sum then,

The cost of a divided Cyprus in northern Cyprus is high inflation, leading to low growth, low incomes per capita and separately weakening independence because of higher and higher dependence on Turkey.

In the south, the cost is energy isolation, which leads to high electricity prices,

The peace dividend would be about €17.4bn at 2020 prices, which is about €20.7bn at today’s prices.

That’s it from me. As you can see I am a walking talking geek on Cyprus.

Go to SapientaEconomics.com to find out about all of my products and services.

Thank you for listening.