Some of the (hideous) development on Greek Cypriot dispossessed land in Trikomo/İskele. Source: Shutterstock.

I am in the privileged position of never having lived through armed conflict, never having been forcibly displaced and, if you don’t count being basically swindled out of 15 years’ of bank savings partly through my own folly by a crafty so-and-so, I have never been dispossessed of my home or other property.

Displacement and dispossession might have happened to ancestor family members way back in the annals of Irish history. But it was only handed down in a generic, “what they did to our kind” way, not a specific, “what they did to us” way.

So this piece is not about whether suing people who unlawfully exploit your property, or trying to get it back, or trying to get something, anything, if you can’t get it back, is the right thing to do. Instead, it is trying to take as disinterested a look as possible at what it will lead to in terms of politics and geopolitics and what the options are.

Displacement and dispossession

For the uninitiated, Cyprus has been politically divided since 1963 and physically divided since 1974. (If you want a 30-minute history, head over to me being interviewed about it here, or get the transcript here, or read the short Oxford University Press (OUP) book by my pal, James Ker-Lindsay, here.)

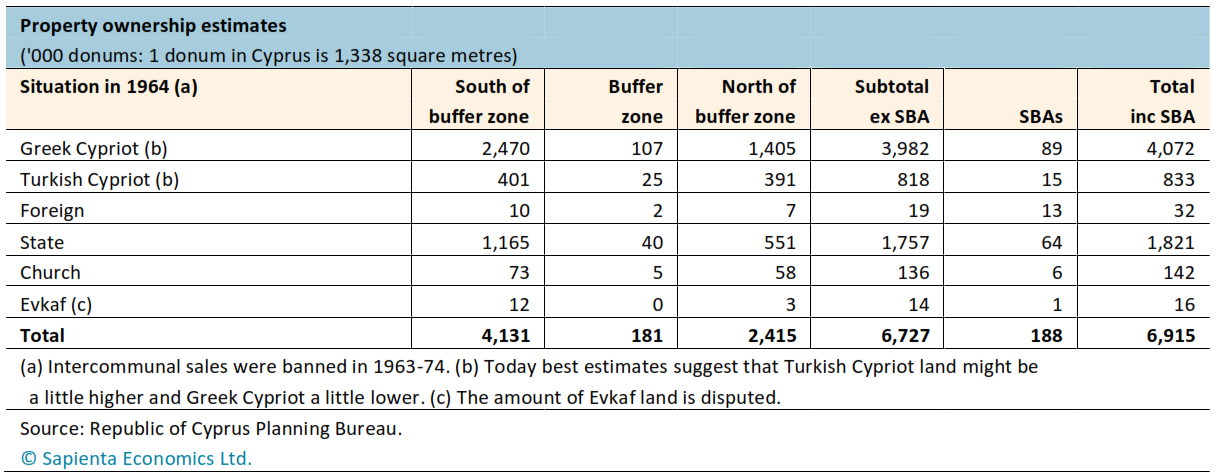

Both communities suffered displacement and loss of property. As of 1974 around 30% of Greek Cypriots had been displaced and around 40% Turkish Cypriots had been displaced. (Sources for these figures are cited on page 3 here.) This meant that a great deal of “dispossessed” or “affected” property, in Cyprob parlance, lies on the other side of the divide. Moreover, the proportion of Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots with affected property has risen over time because of inheritance. Separately, you can infer from all the claims to date that the vast majority of all property at the time of dispossession was undeveloped land.

A non-public portion of the Greek Cypriot property in the north was given to Turkish Cypriots displaced from the south, in return for them signing something to say that they surrendered their property in the south to their new de facto authorities in the north. These are known as Exchange or Eşdeğer titles.

Another, probably smaller, portion was given to other Turkish Cypriots who lost relatives or took part in defending the community. In addition, property was distributed to people from mainland Turkey (generally referred to as settlers), who became citizens of the unrecognized Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). This is generally known as “Greek title”.

Whatever the Turkish Cypriot politicians say, the market apparently knows the difference. Thus, the highest value is original “Turkish title”—land and property always owned by Turkish Cypriots and therefore over which there are no competing claims. The lowest value is Greek title because it has the highest litigation risk. And in the middle is the Exchange title, because so far, at least, the Republic of Cyprus has not gone after the largely Turkish Cypriot “current users” of those properties.

As for Turkish Cypriot property, once upon a time the Republic of Cyprus would have you believe that it was all carefully looked after under the protection of the Guardian of Turkish Cypriot property. But it turns out that Turkish Cypriot property has been mishandled, usurped in more than one case, with apparently little judicial recourse for what has happened.

Continuing possession

In the landmark European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) case of Titina Loizidou, dispossessed property was treated as continuing ownership, not as forcibly expropriated. This means that, under international law, the property still belongs to the person who owned the property when they were displaced.

However, in another landmark case of 2010 known as Demopoulos, and much to the chagrin of Greek Cypriots, the ECHR essentially told Greek Cypriots that instead of taking all cases to the ECHR they must first go to the Immovable Property Commission (IPC) in northern Cyprus—considered by the ECHR as an effective domestic remedy provided by Turkey. Other blows from the ECHR came when a home was essentially defined as somewhere you had lived for at least 10 years (it relied on the notion of “emotional attachment”) and when it said that reinstatement was not the only effective remedy. (If anyone remembers the names of these specific cases please put it in the comments.)

Recent cases brought against individuals

Fast forward to 2025 and a dual Israeli-Turkish citizen is on trial in the Republic of Cyprus government-controlled areas (the Greek-speaking south of the island) for developing €43m worth of Greek Cypriot property in Trikomo/İskele in northern Cyprus.

This has been by far the largest development of Greek Cypriot dispossessed property in northern Cyprus. EU citizens from Hungary and Germany have also been arrested and accused of usurping Greek Cypriot property. There are rumours that the Greek Cypriots will go after Turkish Cypriot developers next: not displaced Turkish Cypriots but people who have made money from Greek Cypriot property.

To say that this has sent the Turkish Cypriot leader and president of the unrecognized Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), Ersin Tatar, hopping mad is an understatement. He has basically told the newly reappointed Personal Envoy to the UN Secretary-General (PESG), Maria Angela Holguin, that she will achieve nothing while the Greek Cypriots pursue this policy, which is clearly having an impact on the property market. There have also been suggestions about closing the crossing points across the UN-monitored buffer zone.

The Greek Cypriots have said that this is a judicial issue; they cannot interfere. Yet it is hard not to conclude that the choice to pursue cases was political. State resources will have been spent on approaching dispossessed owners to ensure they are prepared to sue or confirm that their property has been usurped; on gathering evidence on the activities of those who have now been arrested; and miraculously so far, ensuring that no one has tried to sue any displaced Turkish Cypriot who signed that piece of paper to get an Exchange title.

Meanwhile, Turkish Cypriot politicians have suggested that the correct way to pursue property claims is through the IPC, given that it has been endorsed by the ECHR as an effective domestic remedy (albeit it at a time when it was making payments more quickly).

I assume that the Aykut case, if the defendant survives cancer, will end up in the ECHR, which will decide whether the Republic of Cyprus approach is justified and/or proportionate.

What won’t be achieved

That is where the law and the cases have left us. What about the politics? A few things seem obvious.

No one is going to get their property back this way.

Greek Cypriot dispossessed owners are bound to be awarded more by Republic of Cyprus courts than the IPC but the defendant will doubtless declare bankruptcy and the owners will never see their money.

Some lawyers will get paid.

Some politicians will feel satisfied.

If it gets to the ECHR, bear in mind that the Demopoulos case basically shows that the ECHR was fed up with Greek Cypriots.

Other cases show it will not pay much. In another set of ECHR cases I studied at length, the ECHR found a large number of monetary claims to be “excessive” or even “manifestly excessive” (see Chapter 6, footnote 77 here).

In other words, don’t expect big payouts from the ECHR. I laboriously calculated that people got 15% of their claims on average and barely any legal costs at all. (See Chapter 6, footnote 79 here.)

So what will these cases have achieved?

Reinstatement of property: no.

Big payout: no.

Any kind of just satisfaction for owners: likely no.

A lot of money for lawyers: yes.

A feather in the cap of the Republic of Cyprus government: yes.

Discomfort for Turkish Cypriot politicians and property dealers: yes.

Reduced likelihood of a solution of the Cyprus problem: yes.

Increased risk of the permanent closure of crossing points: yes.

Thereby increased likelihood of full “Turkification” of the north: yes.

Increased risk of Cyprob crises: yes.

Is there another way?

There are no obviously good options but one or two below might work.

Option 1: do nothing and watch the frog boil. One option is to do nothing, wait for Mr Tatar to close the crossing points in revenge (now that more Turkish Cypriots are crossing south than vice versa, he might be tempted), wait for Turkey to take revenge by resuming drilling in the Republic of Cyprus offshore Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), and we find that we have all slid back to 2020 with frequent “Cyprob crises” distracting diplomats and a much worse domestic political situation for Turkish Cypriots.

Option 2: kid ourselves negotiations are near. Another is to fantasize about getting back to the negotiating table soon. Even if we end up with a new leadership in northern Cyprus after October, the most pro-solution Turkish Cypriots’ conditions for returning to the table have toughened after what they saw as a betrayal in Geneva and Crans Montana in 2016-17. Negotiations are therefore highly unlikely, so “solve the Cyprob within a year” is not a realistic option.

Turkey option: offer quick financial carrots. Tactically, to prepare itself for possible ECHR cases, Turkey could ramp up staff at the IPC and launch an online mass claims process. Greek Cypriot dispossessed owners would perhaps get faster money if they accept an offer based on generic characteristics and would not be forced to open Turkish Cypriot bank accounts to get their money. However, for years the question of who funds the IPC has been stuck in an argument between northern Cyprus and Turkey. Therefore, it is not clear that there is any will to do this, especially given that the outcome in terms of litigation will still be uncertain without any final say from the ECHR.

Option 3: refer the question to the ECHR (ECJ-style). Ideally you would want the ECHR equivalent of a European Court of Justice (ECJ) referral, where you ask whether cases have to go to the IPC first before the Republic of a Cyprus authorities can pursue a criminal case against a seller or developer of Greek Cypriot property. It would need diplomacy to ensure that cases in the south and large-scale development in the north were paused while the ECHR deliberates. Are diplomats ready to do that footwork?

Option 4: ask the citizens how they want to approach it. Another option is my old chestnut, outlined towards the end of last week’s article, namely to bring in the people. What if we were to ask citizens, over a period of weeks and in a professionally managed way, to propose options on a property settlement? And to propose a property settlement that is not totally dependent on a comprehensive settlement so does not have to wait?

Would they come up with more workable solutions than the politicians? As I discussed in this podcast here, research on different types of Cyprob solution suggest they would indeed be more flexible.

If you want my premium monthly in-depth product, check out Sapienta Country Analysis Cyprus and other deep-dive reports here. And if you can’t afford that but want the executive summary only for just €100/year, you can find that here on Substack, at Cyprus Pocket Brief.

Or keep these articles and hugely labour-intensive videos coming by supporting this publication, Sapienta Cyprus Snippets, for just €49 per year.

Correct. Whoever “invests” in North Cyprus by buying stolen Greek properties,

will surely loose them in International Court; there is a legal precedent.